That is the question when one has had enough of glasses, contact lenses, and blurry vision. Whether to correct myopia, hyperopia, or astigmatism, LASIK is the most popular elective eye surgery used to treat these ailments. However, while elegant in its simplicity, it isn’t right for everyone.

A while ago, I considered undergoing the procedure. Following the promise of a cozy life free of glasses and contacts, I dug into the rabbit hole. I went from how it works and how it emerged to its risks, costs, and true capabilities. I share my findings in this article in the hope that those interested in LASIK can discover the basics at length.

What is LASIK?

LASIK is the acronym for laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis. It is an eye surgery where a special cutting laser removes tissue from the cornea in order to correct refractive errors—up to -12 diopters of nearsightedness, +6 diopters of farsightedness, and 6 diopters of astigmatism.

In order to better understand how LASIK works and what it does, we first need a basic understanding of the aforementioned refractive errors.

Refractive Errors

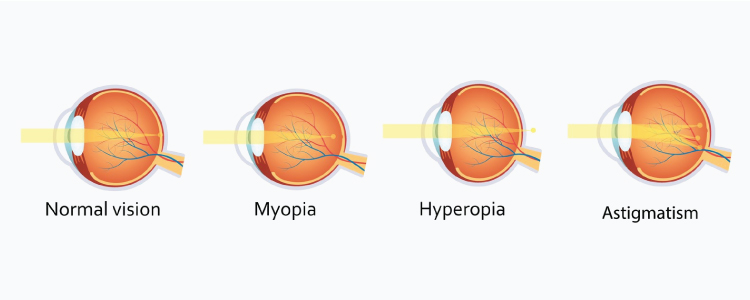

For us to see, light must go through the cornea and the lens in order to reach the retina, right at the back. This thin layer of tissue receives the light, converts it to neural signals, and sends them to the brain via the optic nerve. However, if there is a problem with either the cornea or the lens that causes the light refraction to misalign, a refractive error ensues. As a result, objects will look blurry, depending on the nature of the misalignment.

With myopia (nearsightedness), far-away objects look blurry due to the eyeball being too long from front to back, which causes the light to focus at a point in front of the retina. Hyperopia (farsightedness), on the other hand, makes nearby objects look blurry due to the eyeball being too short from front to back, which causes the light to focus at a point behind the retina. Astigmatism is a problem with the shape of either the cornea or lens that causes the light to focus incorrectly.

A Centuries Old Fight Against Blurred Vision

Refractive errors are nothing new, though. More than two thousand years ago (350 BC), Aristotle coined the term myopia—muoops, derived from muein “to close” and oops “the eye”—alluding to the habit of short-sighted people to squint in order to focus faraway objects better. Back then, people dealt with blurry vision with the use of magnifying lenses to see small text. They also discovered that some types of lenses helped with specific visual problems: convex lenses helped with hyperopia, while concave lenses helped with myopia.

Later, during the Middle Ages, people in Italy came up with the idea of inserting these lenses into frames. Such was the birth of eyeglasses, which soon became the only medium to help people see better during the centuries that followed.

But the quest for more practical and aesthetic visual aids never stopped. During the XIX century, inventors almost raced to develop lenses that could be placed directly over the eye itself. Adolf Gaston Eugen Fick won in 1888 with the first scleral contact lens.

Glasses and contacts have helped us correct refractive errors ever since. However, after all the technological and scientific advances there are today, why is there no cure for refractive errors? History seldom offers simple answers. In this case, the lack of answers may have been influenced by the fact that ophthalmologists didn’t actually consider refractive error a disease until recently.

The Birth of Keratomileusis

That attitude wasn’t part of Spanish ophthalmologist Jose Ignacio Barraquer Moner‘s worldview. According to him, if an organ doesn’t work properly, it must have a disease, so it should be cured. Glasses and contacts were mere prosthetics that reduced quality of life, in his opinion. People depended too much on them. Losses or malfunctions came at a great cost and were a cause of great concern and stress.

In 1948, he had the idea of modifying the corneas of individuals in order to permanently correct refractive errors. After many years of research into the topic, he introduced the term keratomileusis (sculpting of the cornea) in 1964.

This procedure entailed removing a disc of corneal tissue, freezing it in liquid nitrogen, and milling it using a modified watchmaker’s lathe in order to achieve a certain corneal curvature that could refract light correctly. Afterward, the tissue would be reattached.

Shape of the cornea after keratomileusis for A) myopia and B) hyperopia

The procedure was riddled at first with operational and logistical problems, though. Firstly, the corneal tissue removal relied heavily on the tool used and the stable hand of the surgeon. Second, the frozen cornea needed transportation to another building where the milling could take place. Third, the reattachment needed stitches.

Fortunately, Moner and his students perfected the procedure during the subsequent decades. So much so that, in time, the popularity of keratomileusis increased. However, it wasn’t until the 1980s that the necessary pieces fell into place to give birth to what we now know as LASIK.

Flaps & Lasers

The first piece was the discovery of photoablation—typified by excimer lasers. These lasers generate intense ultraviolet energy beams, which disintegrate tissue into molecular fragments. While these fragments get ejected from the site at high velocities, the process leaves adjacent tissue unaffected. This made the use of lasers for eye surgery a more precise and less harmful option that also improved recovery.

The second piece came when other surgeons realized that removing a slice of the cornea wasn’t necessary. Instead, they cut a flap that remained attached by a tiny amount of tissue. After making the necessary corrections, they could easily place the flap back on and let it heal without stitches.

The third piece was an accident. During one of Dr. Luis Ruiz’s many keratomileusis on schedule, he made a corneal cut that was too thin for the procedure. The patient’s time would have been wasted had he not realized that he could still remove enough tissue from what was left of the cornea to achieve the required refractive correction. With a few calculations and what I imagine was a really steady hand, he succeeded. After Ruiz published his discovery in 1988, keratomileusis officially became in situ (from Latin, on site or in position).

Afterward, various publications about the use of lasers to ablate tissue under a corneal flap emerged across the world. Aleksander Razhev corrected four myopic and five hyperopic eyes with this technique in 1988. Lucio Buratto did it too in 1989 with 30 high myopic eyes. The procedure had to wait for its modern connotation until 1990, when Pallikaris coined the term laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis to describe it.

LASIK Step by Step

LASIK’s technique hasn’t changed much since. Precision lasers became even more precise, and better standards for patient care emerged. Patients nowadays have a relatively comfortable and unproblematic experience and often enjoy good results.

Let’s now have a short look through the procedure, starting with its requirements (section sources: 1, 2, and 3).

Before LASIK

Before agreeing to submit the patient’s corneas to the lasers, good surgeons make sure that candidates:

- have a thick enough cornea to sustain the required correction,

- have appropriately sized pupils, since patients with larger pupils are more likely to experience issues with night vision and glare,

- have a stable prescription for at least 1 or 2 years (the longer, the better),

- be at least 18 years old (or 21 in some cases),

- have good eye health (no dry eyes, no cataracts, glaucoma, diabetes, or autoimmune diseases).

When the surgeon is convinced LASIK is appropriate for the patient, an appointment will be set. Then, the surgeon will ask the patient:

- not to use contact lenses several weeks before the surgery, and

- not to use make-up 24 hours before the procedure.

During

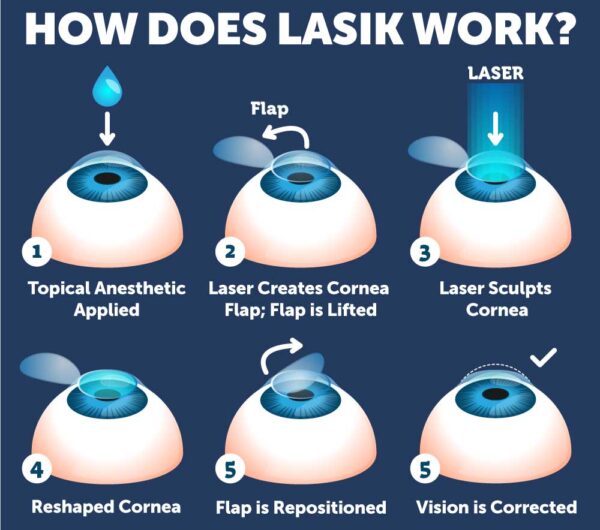

The procedure lasts up to 30 minutes, during which the patient is fully conscious. This is necessary because there is no way of guaranteeing the eye will be still for the surgery if the patient is asleep. Surgeons will offer medication to help patients relax, if required.

The surgeon will start by applying eye drops to numb the eye. Then, he will place an eyelid holder and a suction ring to keep the eyelids and the eye still. This creates a feeling of pressure on the eye and causes vision to dim or turn black.

He will first use the laser (or microkeratome) to create the corneal flap. After lifting it and exposing the tissue underneath, he will then ask the patient to stare at a light right in front of him while he sets to work on the exposed cornea with the help of the laser. When the correction is done, the surgeon puts the flap back into place, which settles within minutes and starts self-healing.

After

Though many patients return to normal activities within days, the actual recovery time of LASIK is estimated to be 3 to 6 months.

Right after the surgery, the eyes might itch, burn, feel gritty, and be watery. Vision will be blurry as if one were looking underwater, but this normally improves very quickly.

Nevertheless, for the eyes to heal properly, patients need, first and foremost, to keep up with follow-up appointments. Also, they are to refrain from touching or rubbing their eyes and will probably require eye drops for dry eyes with antibiotics or steroids. Some patients might need a shield over their eyes during sleep.

For the weeks after the surgery, patients need to avoid wearing makeup and engaging in contact sports. When it comes to showers, baths, and swimming, patients need to either ascertain that the water is not contaminated or simply avoid it. Goggles offer some protection for swimming.

Risks

Like any other surgery, LASIK comes with its own set of risks, side effects, and complications. Let’s look at the most common ones and their causes.

Dry Eyes

There’s an area on our bodies that contains 300 to 600 times more nerve density than the human skin: our corneas. This sheer amount of nerves is necessary so that the cornea can provide the sensations of touch, pain, and temperature responsible for triggering blinking, wound healing, and tear production and secretion. These nerves are severed during LASIK, which reduces the amount of sensation they transmit. This causes the eye to not sense the need for moisture and produce fewer tears, which causes dry eyes.

Almost all patients will develop these symptoms after LASIK, but in most cases, they will resolve over time. In about 60% of cases where patients suffered from dry eyes before undergoing LASIK these symptoms disappeared. About 20% of patients can suffer persistent symptoms of chronic dry eyes six months after the surgery, though. Most at risk are women and those who need a very big refractive correction.

Poor Night Vision

As mentioned before, problems with glare, halos, starbursts, and poor night vision come into play more frequently for people with larger pupils. As we know, pupils dilate in low-light conditions in order to let the most light possible through. Patients with large pupils that dilate beyond the area of the cornea that the laser modifies will see glares and halos around lights. This affects their vision in low-light conditions.

In order to prevent this, eye surgeons carefully measure pupil size and determine if they can treat a large enough area of the cornea before the surgery. But if the symptoms appear regardless, they are manageable with eye drops that prevent the pupil from fully dilating or by changing light conditions during the night.

Other Risks

Other risks and possible complications worth taking into account include:

- Under-corrections. When the laser removes too little tissue. It happens more commonly with nearsighted people and may require another surgery.

- Over-corrections. When the laser removes too much tissue.

- Astigmatism. The tissue removal is uneven, which may also require another surgery, glasses, or contacts.

- Flap problems. The flap created during the surgery can result in infection and excess tears. Sometimes, the corneal layer grows abnormally underneath the flap during the healing process.

- Vision loss or changes. Sometimes people won’t see as sharply or clearly afterward.

- Central ocular neuropathic pain. It can be a result of nerves healing incorrectly.

Though symptoms like dry eyes can be managed with eye drops and complications like glares and halos can be overcome, the discomfort they may cause can affect quality of life after the surgery. This is to say that all risks are worth thinking about before undergoing the procedure. The good news is that one can avoid risks and complications quite simply by choosing a good surgeon. The American Refractive Surgery Council gives some tips on how to make the best choice.

Curb Your Enthusiasm

While LASIK was born from the desire to cure refractive error, it actually can’t achieve it. To cure an illness, one must usually understand the underlying causes and develop a treatment to restore the affected system to a healthy state. Sadly, the causes of myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism weren’t well understood in Moner’s time (and still aren’t). While LASIK corrects the existing refractive error at the time of the procedure, it can’t prevent it.

Presbyopia

Let’s start with the inevitable. Presbyopia is a refractive error where nearby objects start looking blurry as we age due to the loss of flexibility and hardening of the lens. All older adults develop some level of it and will need glasses or contacts to improve their vision. Presbyopia starts on average at 40 years of age and progresses until one is about 60.

Those who had LASIK earlier in life could consider undergoing the laser again with monovision LASIK or SUPRACOR LASIK. However, another surgery might be out of the question since their cornea might not be thick enough for a second procedure.

But if LASIK is done early enough, people could theoretically enjoy several years free from visual aids. That is, if regression doesn’t happen.

Regression

Regression is traditionally defined as residual myopia or hyperopia of 0.25 D or greater between follow-up visits after LASIK. Its causes are poorly understood, but it is theorized that it involves the mechanisms the eye uses to heal the cornea. When there is an aggressive refractive correction, the eye seems to have an equally aggressive corneal reparation response, which may undo part of the correction.

Our lack of better knowledge on regression leaves us with limited mechanisms to prevent it. So far, all we can do is quantify its incidence as best we can.

Here are some educated guesstimates:

- For people with hyperopia, the incidence is about 30% during the first postoperative year, though progression stabilizes afterward (sources: 1, 2).

- For people with myopia, regression in the first operative year has been reported between 7% and 21% of the time— higher if the patient has chronic dry eyes. Like with hyperopia, it is expected to stabilize after the first year. However, those with medium to high myopia (> 6 D) run a higher risk of regression (sources 1, 2, 3).

Progression

Assuming regression isn’t a problem, LASIK permanently corrects the refractive error that exists in the eye at the time of the procedure, but it doesn’t stop its natural progression.

The rate of progression depends on age and lasts decades, but the good news is that it eventually stabilizes. Myopia is the error most prevalent in school-age kids and tends to progress at a faster rate than hyperopia. Both errors peak at around 8 years of age and tend to stabilize at 26–27 years of age. If the progression of the refractive error hasn’t stabilized by the time one undergoes refractive surgery, the eye will continue to develop the error, and the procedure will seem to have been for naught.

Especially patients with high myopia need to be aware of the high chance of the refractive error coming back because they tend to suffer from a similar rate of progression irrespective of age. This does not mean they can’t have LASIK, but it does mean that their expectations need to be realistic.

Price

Like everything in life, LASIK comes at a price. The procedure costs between $1,000 and $4,000 in the US, with the average being $2,632 per eye. Here in Germany, prices range from 750 euros to 2,000 euros. Unless insurance pays for the surgery, the majority of people will have to save up or take out a loan in order to afford it.

But despite the high cost, LASIK receives praise as a money saver. After all, while it can’t grant us a life free from visual aids, its best results eliminate their costs for many years.

In order to determine if the procedure would be financially convenient in my case, I sat down and did some back-of-the-envelope math. If I were to undergo LASIK I wouldn’t do it in a clinic with the cheapest price, so I would pay about 2,000 euros for both eyes. I would not need contacts or glasses again until presbyopia starts, which is 9–14 years from now. I currently spend about 100 euros a year on contact lenses, so LASIK would “save” me a maximum of 1,400 euros—not even enough to offset the cost of the surgery. Once presbyopia starts, the costs of either glasses or contacts for it will just add up.

Then again, this is my case. LASIK might make financial sense for others who don’t need to pay out of pocket, or for those who need very expensive glasses.

So, it’s not Worth it Then…

To be fair, glasses and contacts aren’t mere prosthetics that hinder people’s quality of life, as Moner would put it. Glasses improve people’s vision and quality of life while also being, at the same time, fashion statements and status symbols. In parallel, contacts do the same while remaining almost imperceptible.

Both have undeniable upsides, but they aren’t perfect. Glasses can constantly fall a little down the nose and require a pushback up, however well-fitted they are. Sports, sleeping, taking showers, swimming, or going for amusement park rides require their removal for safety or practicality. Prejudice exists against glasses and those who wear them too, making them targets for mockery and bullying. Contacts require hygiene, care, and constant replacement. Failure to properly clean them and/or replace them on time can lead to eye infections and other complications that damage the eye. Also, their costs add up in our wallets, and their waste adds up in landfills and water supplies.

Moreover, Moner was right in that we, the cursed ones, who suffer from refractive errors, are very dependent on our visual aids. When they break, get lost, can’t be provided, or can’t be afforded, our quality of life becomes impaired. The elimination of this dependence—for a time—is worth it for some people, despite the costs and risks of refractive surgery.

Personally, though, I have decided against it. I wanted permanent freedom from glasses and contacts and thought LASIK would guarantee it. But finding out that I would inevitably wear visual aids again discouraged me. Also, the financial terms didn’t sway me towards it either. In my case, the short-lived freedom from visual aids doesn’t justify the costs and risks.

Conclusion

LASIK is a simple and modern eye surgery that can correct refractive errors to the undeniable satisfaction of most patients. While relatively straightforward, it has its risks and limitations, like any other surgical procedure. Anyone willing to consider refractive surgery needs to evaluate such a decision, taking into account their expectations, desires, finances, and health.

After all, refractive surgeries aren’t always the best choice. While studies (1,2,3) that survey, quantify, and compare the self-reported quality of life improvements in people who use glasses, contacts, or underwent refractive surgery agree that those who had refractive surgery reported higher improvements, glasses and contact users also reported quality of life increases.

With that in mind, it is my hope that the information compiled in this article informs readers about LASIK well enough so that they can make the best individual decision.

In the end, it doesn’t matter if one uses glasses, contacts, or refractive surgery to see the world clearly. We only have one pair of eyes and should make the best of them at any age and in any way we can.